Laser Destroys Cancer Cells Circulating in the Blood

The first study of a new treatment in humans demonstrates a noninvasive, harmless cancer killer

By Emily Waltz.

Published in the June 12, 2019 issue of IEEE Spectrum

Tumor cells that spread cancer via the bloodstream face a new foe: a laser beam, shined from outside the skin, that finds and kills these metastatic little demons on the spot.

In a study published today in Science Translational Medicine, researchers revealed that their system accurately detected these cells in 27 out of 28 people with cancer, with a sensitivity that is about 1,000 times better than current technology. That’s an achievement in itself, but the research team was also able to kill a high percentage of the cancer-spreading cells, in real time, as they raced through the veins of the participants.

If developed further, the tool could give doctors a harmless, noninvasive, and thorough way to hunt and destroy such cells before those cells can form new tumors in the body. “This technology has the potential to significantly inhibit metastasis progression,” says Vladimir Zharov, director of the nanomedicine center at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, who led the research. “This technology has the potential to significantly inhibit metastasis progression.” —Vladimir Zharov, University of Arkansas

The spreading of cancer, or metastasis, is the primary cause of cancer-related death. Cancer spreads when cells from primary tumors break off and travel through the bloodstream and lymph system, settling in new areas of the body and forming secondary tumors.

Killing these circulating tumor cells, or CTCs, in the bloodstream before they have a chance to settle could help prevent metastasis and save lives. Simply being able to count CTCs could help doctors more accurately diagnose and treat metastatic cancer—something no device has been able to do efficiently.

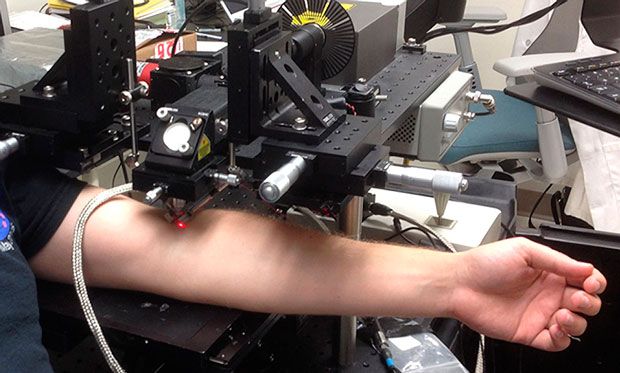

Zharov and his team tested their system in people with melanoma, or skin cancer. The laser, beamed at a vein, sends energy to the bloodstream, creating heat. Melanoma CTCs absorb more of this energy than normal cells, causing them to heat up quickly and expand.

This thermal expansion produces sound waves, known as the photoacoustic effect, and can be recorded by a small ultrasound transducer placed over the skin near the laser. The recordings indicate when a CTC is passing in the bloodstream.

The same laser can also be used to destroy the CTCs in real time. Heat from the laser causes vapor bubbles to form on the tumor cells. The bubbles expand and collapse, interacting with the cell and mechanically destroying it. Imagine shooting bad guys in video games, or shining ultraviolet light on bacteria. If that kind of thing feels good to you, imagine how satisfying it would be to point this laser at your loved one’s cancer cells.

The purpose of the study published today was to test the accuracy of the device in detecting CTCs. But even with the laser in a low-energy diagnostic mode, it killed a significant number of CTCs in six patients. “In one patient, we destroyed 96 percent of the tumor cells” that crossed the laser beam, says Zharov. He and his colleagues say they hope the laser will be even more effective when they turn up the energy in future studies.

Zharov came up with the idea for the technology more than a decade ago, and since then has been testing it in animals and demonstrating its safety to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), whose approval was required before proceeding with the clinical trial. Zharov says the device is the first noninvasive CTC diagnostic to be demonstrated in humans.

At least a hundred other devices designed to monitor CTCs have been proposed. These systems typically involve drawing blood from a vein and analyzing it outside the body. Only one such device has received approval from the FDA: a machine called CellSearch that’s about the size of an oven. It handles small samples of blood, providing only a snapshot of the CTCs that might be present in the whole bloodstream. Consequently, this kind of diagnostic isn’t broadly used in standard cancer care.

Researchers at the University of Michigan in April announced that they had made progress on this front. Their wrist-worn device pumps blood out of the body, captures CTCs, and then pumps the cleansed blood back into the body. Still, in a study in dogs, the device only processed a couple of tablespoons of the animals’ blood over two to three hours.

Zharov’s device can examine a liter of blood in about an hour, without the blood ever leaving the body. Its sensitivity is about a thousand times greater than that of CellSearch, the researchers reported. Next Zharov and his colleagues are testing the device on a larger human population, and combining it with conventional cancer therapies to see the effects on metastasis.

The photoacoustic effect, by the way, was first described by Alexander Graham Bell in 1880, when he transmitted vocal signals in an invention called the “photophone.” Zharov’s team dubbed their device the “cytophone.” (Get it? “cyto-” means “of a cell.”)